It is no coincidence that “culture change” is the number one strategic challenge for most CEOs and why corporate transformation programmes abound. It is also the reason why so many good people leave corporate life to set up on their own.

We all want employees who are open and creative, yet all-too often we cause them to close down or to create unnatural personae as a means to protect themselves from the politics which we (unwittingly?) create.

I was fortunate to learn my ‘cultural’ lesson early in my career, although it didn’t feel fortunate at the time. My first job out of university was in product development for a large food manufacturer; one where bored senior managers whiled away their time and jockeyed for position by pitting their departments against each other. This was particularly the case between Production and R&D and working between the two, I was soon in the firing line.

One day, whilst walking through the factory to my office, I came across a friend of mine who was standing by a long oven which had smoke and tons of burnt product, pouring out of it. The conversation went like this:

“Hi Si. What’s up?”

“Someone’s changed the temperature settings. Probably the new Shift Manager. She only started last week.”

“Anything I can do to help?”

“No. I’ll deal with it.”

So off I went to my office: a 10-minute walk. When I got there, my boss was standing outside, hands on hips, looking angry.

“Hi Ron. What’s up?”

“I would like a word with you. The Production Director’s been on the phone. He told me you’ve just burnt a whole batch of sausage rolls. We are having to pay the bill. I’m not happy”.

That evening I met my friend Si for a beer.

“Si. What happened today? I got it in the neck from Ron for something I didn’t do? How come I got the blame for the burnt sausage rolls?”

“Yeah sorry, but (the Production Director) needed a patsy and you fitted the bill. Don’t worry about it. This happens all the time. You’ll get used to it”.

Well I never did get used to it and like so many people I quickly left that company for cleaner, fresher air. And surprise, surprise, my ex-employer didn’t last too long. The politics killed it and although the factory still remains, the business entity that owned it quickly disappeared into oblivion.

So, what’s the lesson here? Could the business have changed? Could my leaving and that of my many similar colleagues have been prevented?

In my view yes, but only with firm leadership. Not even a great operational excellence system like Isoma, which is so often used to accelerate culture change, could have made much of a difference there. The issue was rot at the top: poor leadership that allowed a corrosive culture of game-playing politics to emerge and then dominate the business, so it became toxic from the top, down. The senior management team liked the status quo: they enjoyed the game-playing and for reasons that will forever remain unknown to me, the CEO tolerated it and may have been blind to its effects on everyone else.

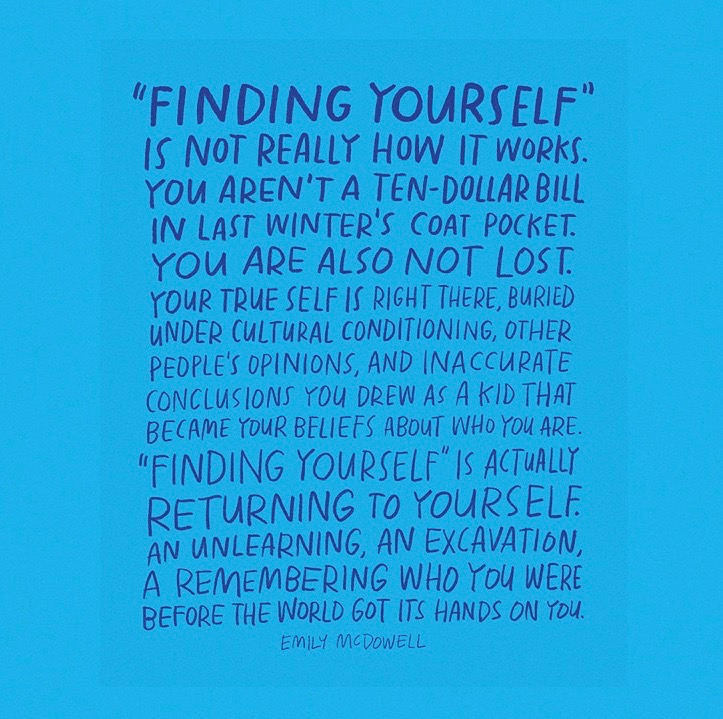

Every business wants employees who are open and creative and when I joined that business, that is just what I was: every bit as keen as today’s Millennials to make a difference. But as Emily Mc Dowell concluded, the world got its hands on me: in this case my closeted corporate world of the time. We still did some great things, not least of which was the creation of the World’s first sandwich production line and from a personal perspective that little incident with the sausage rolls was a significant factor in me launching my own food factory. But with a different culture, just think what more we could have achieved.